Have joint pain? Start here.

A conversation about joint pain, aging, and what’s actually within our control.

Joint pain has a funny way of sneaking up on us. It often shows up gradually: a hip that aches longer than usual after a run. A low back that quietly dictates how long you can sit, walk, or stand without thinking about it. A knee that just… doesn’t feel right. We’re told this is just part of getting older, and over time, many of us stop questioning it and accept it as part of life.

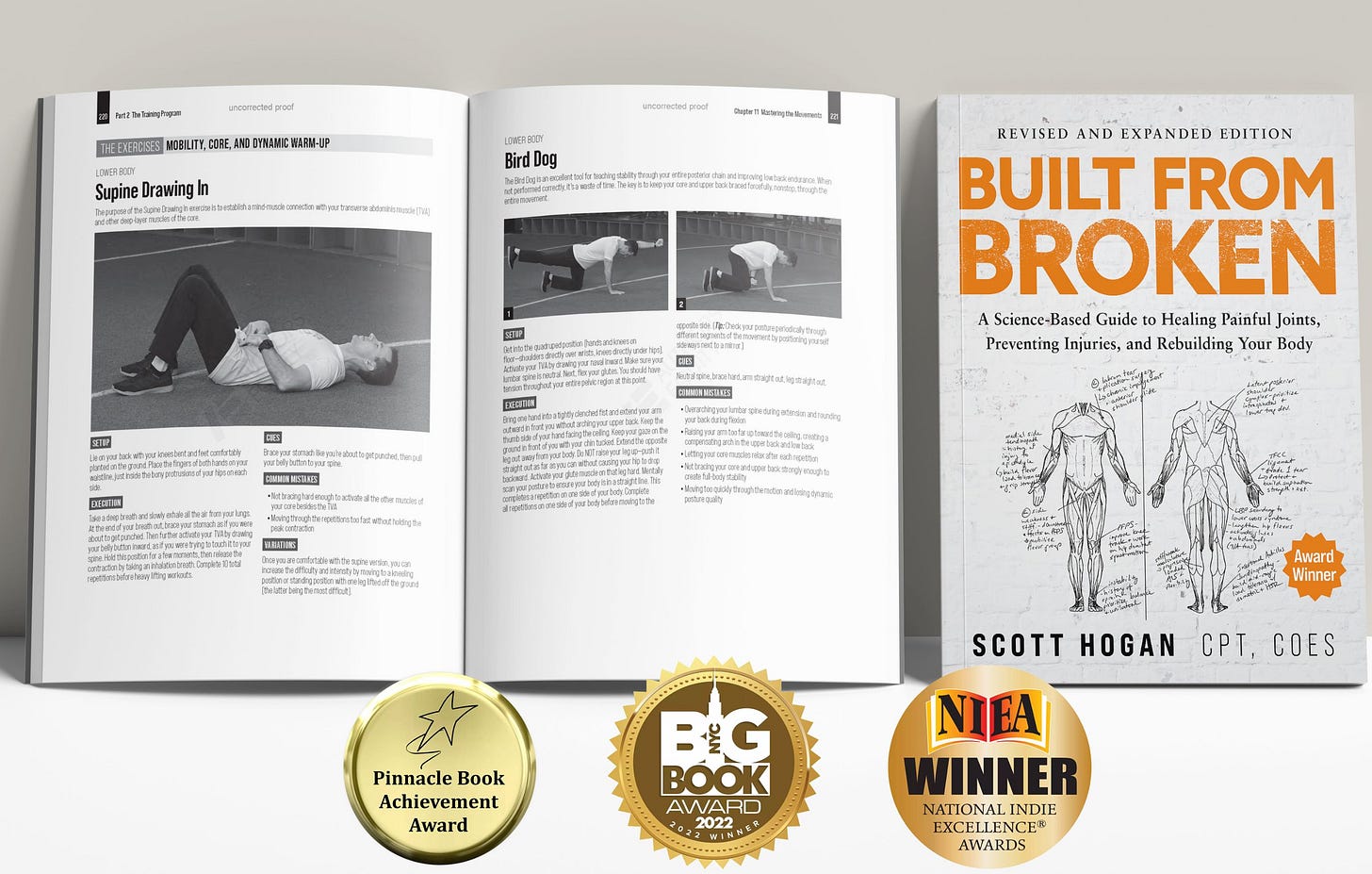

Built from Broken by Scott Hogan approaches pain differently. Instead of asking how to manage it, Scott asks why so many bodies break down in the first place—and what’s actually within our control. He challenges the idea that discomfort is inevitable, or that the only options are rest, medication, or doing less of what we love.

Since Scott self-published the book in 2021, it’s reached nearly a million readers who were looking for something more practical—and more hopeful—than “learn to live with it.”

Below is my conversation with Scott Hogan about why joint pain is so often misunderstood, how well-intentioned routines can work against us, and what it looks like to rebuild strength and mobility in a way that lasts.

—Carly

Carly Gorga: A lot of people assume that joint pain is just part of getting older. What are some of the most common pains you see that feel inevitable—but actually aren’t?

Scott Hogan: This is the crux of the problem—people accept joint pain as normal. There’s a lot more we can do than people realize to tilt the scales in our favor.

The first thing to understand is that the vast majority of joint pain occurs in, or stems from, what I call the Big Three joints: the low back, knees, and shoulders. If we can bolster these joints and improve mobility around them, most joint pain throughout the body resolves on its own.

The second key concept I talk about in the book is tendon-related pain. Roughly 60–70% of non-arthritic joint pain is actually tendon pain—not cartilage, ligaments, or other tissues, but tendons, which connect muscle to bone. Of that tendon pain, about 90% is caused by repetitive-use overload.

So we’re left with a pretty eye-opening takeaway: fix and prevent repetitive-use tendon injuries, and you’ve addressed roughly 80% of joint pain. That’s the Archimedes lever for managing healthy joints throughout life.

CG: Many people are active—they walk, do yoga, spin, or run—and yet something always hurts. What are the warning signs that a “healthy” routine is quietly breaking the body down instead of building it up?

SH: This is an important and very common challenge.

In the age of cold plunges, massage guns, and regenerative therapies, I’m seeing more people cover up root-cause problems with surface-level recovery aids. Put simply: if your exercise program requires anti-inflammatories or recovery tools just to keep you functioning, something is wrong with the program.

The most telling warning sign is pain from exercise that doesn’t resolve within 24 hours. That’s a signal your body isn’t recovering properly, or that you’ve overextended and are drifting toward repetitive-use injury. An elevated resting heart rate first thing in the morning is another good indicator that your system is running on fumes.

Interestingly, the solution isn’t always more rest—it’s often better countertraining against the habits that lead to injury. For example:

A regular golfer needs to mobilize and strengthen muscles that aren’t used during their swing.

An office worker needs to mobilize the hips and fronts of the shoulders to counteract habitual slouching at a keyboard.

This kind of countertraining helps prevent asymmetries from turning into repetitive-use injuries over time.

CG: You’re skeptical of stretching as a solution for tightness, which will surprise a lot of people. If someone stretches regularly and still feels stiff or achy, what’s really going on beneath the surface?

SH: There are a few problems with stretching as a solution to joint pain. First, it’s important to distinguish between dynamic stretching—moving through a full range of motion repeatedly—and static stretching, where you hold a stretch for 20 seconds or longer. Most of the research focuses on static stretching, and it’s not particularly encouraging. Some studies even suggest stretching before exercise can increase injury risk and reduce strength.

From a behavioral standpoint, static stretching is also boring for most people, which means adherence is very low. I’m much more in favor of dynamic stretching, where you move in and out of positions five to ten times.

But the bigger issue is stretching without purpose. People often end up stretching muscles and joint systems that are already unstable. The better approach is targeted: identify which joints need stability and strength, and which need mobility, then address each accordingly. The blanket strategy of “stretch everything” just doesn’t work well in real life.

CG: The book emphasizes that you can rebuild your body with surprisingly little time. If someone trains just two or three days a week, what has to be true for that time to actually improve joint health?

SH: It’s a common misconception that daily or near-daily training is required for exercise to be effective. Research shows otherwise. Studies of untrained seniors, for example, demonstrate that just two days of resistance training per week can deliver the same strength gains as four or five days—if it’s done purposefully.

When training only two or three days per week, each session needs to pull on two key levers:

A functional warm-up that mobilizes common tight muscles and problem joints

Resistance training designed to improve connective tissue resilience and overall strength

If someone does that even twice per week, and adds variety of movement into everyday life, they’ve stacked the deck in their favor for warding off joint pain and degeneration.

CG: You promise that people can feel meaningfully different in 4–8 weeks. What are the first changes someone should notice if the process is working—and what do those early wins signal about long-term recovery?

SH: I truly believe people can see dramatic improvements in 4–8 weeks, whether they’re new to exercise or longtime fitness enthusiasts.

First, people should feel good leaving a workout—whether that’s at the gym or at home. Not broken down or exhausted, but energized and activated. That’s an immediate indicator the session was successful and helps build momentum.

Second, most people are stuck because they’re avoiding the main constraint in their system—their biggest bottleneck. We gravitate toward what feels good and what we’re already good at, but progress there is incremental. When you instead address unstable joints or mobility restrictions head-on, improvements in both performance and pain can be dramatic.

What surprises people is how enjoyable this process is. Strengthening the weakest link tends to improve everything else automatically. Resolve low back pain, for example, and suddenly movements feel easier across the board—not just in the lower body. The old saying applies here: a chain is only as strong as its weakest link.

The challenge is that the weak link isn’t always obvious. That’s why, in the book, I lay out a step-by-step system for identifying and fixing those constraints—and for changing habits so joint-damaging issues don’t keep cropping up in the future.

Solid interview. The insight about repetitive-use tendon overload accounting for most joint pain reframes the whole conversaiton. That point about needing recovery tools just to keep functioning being a red flag is especially sharp. I caught myself doing exactly that last year before realizing my routine was the problem not my recovery.